If my latest reading is to be believed, the message part.

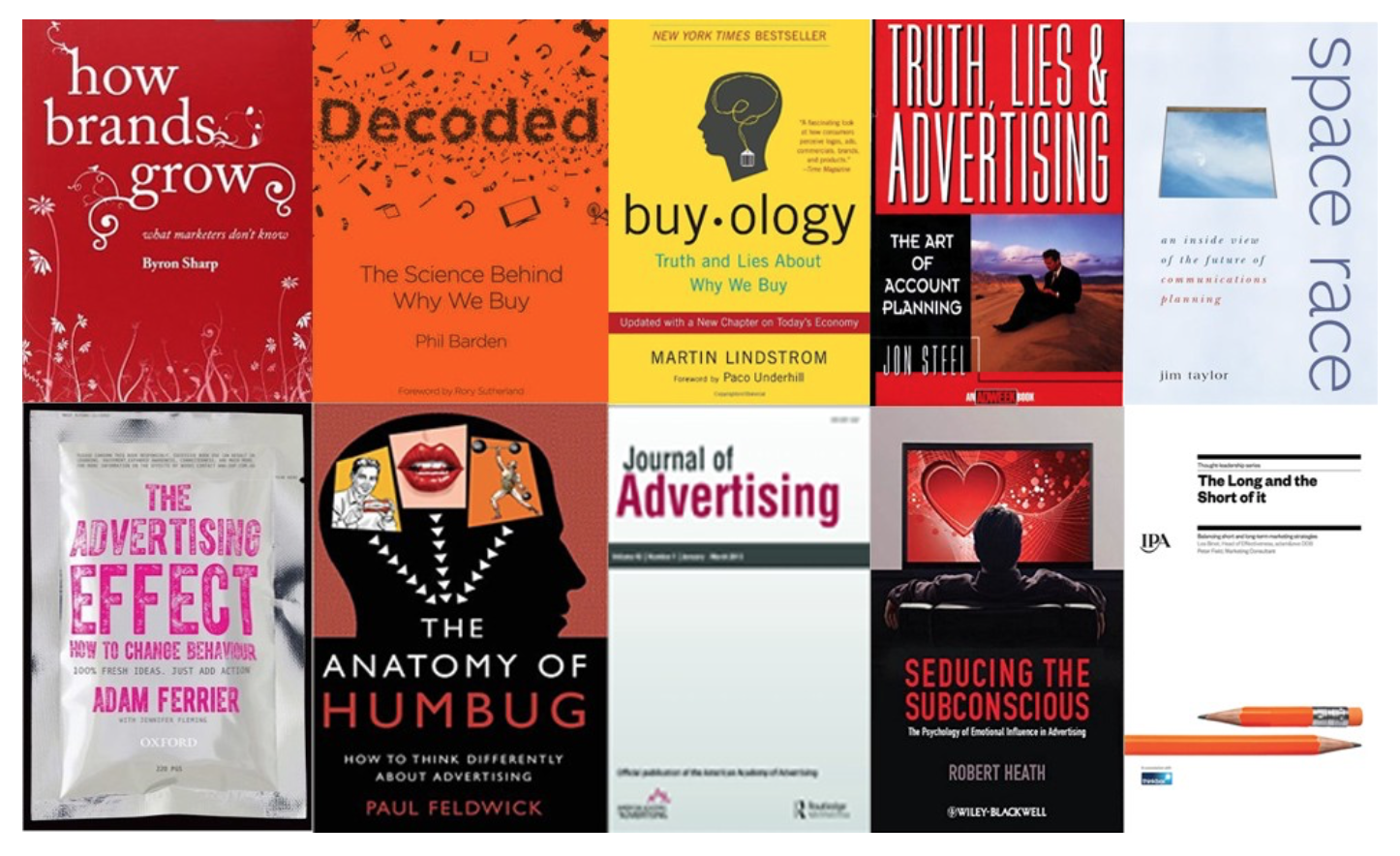

Having recently read and reviewed the excellent ‘The Anatomy of Humbug’ by Paul Feldwick, I was drawn to some of the Author’s references for a deeper dive into the mystery of how advertising works.

Feldwick’s book had already convinced me that the subconscious was the place to look, and so Robert Heath’s ‘Seducing the Subconscious’ was a natural choice. Dr Heath has been one of the most eminent explorers of the psychological processes linking advertising to behaviour change (which for our, and the Author’s purposes translates as ‘buying our brand’).

My real motive is to better understand and explain how my own field of branded packaging works, because I’ve always seen packaging as a media channel. It’s a medium that operates very much unsuspected of any ‘persuasion’ and so, extrapolating the conclusions of this book, has the potential to deeply affect attitudes and behaviour towards brands. It’s frequently been packaging design, not advertising, that has disrupted categories, established new codes, seduced consumers and in the process created new brand leaders.

In this book Heath quickly dismisses both the historic and the modern ‘politically correct’ forms of the ‘advertising as persuasion’ model, and moves on to construct a convincing alternative based on ‘subconscious seduction’. To do this requires understanding of the complex inter-relationships between perception, attention, memory, consciousness, emotion and finally decision-making. Dr Heath achieves this with forensic skill, and as the weight of evidence builds, the book assumes the page-turning qualities of a whodunnit novel.

Despite the mounting evidence against it, there has been a remarkably strong adherence to the persuasion model of advertising. This stems from three sources: a still highly sensitive reaction to the idea that advertising manipulates our actions without us being consciously aware of the fact; the mistaken belief that the creativity which clients value so highly from agencies is there to get people to pay attention to advertising; and finally, a very large and profitable industry (advertising research) that has been delivering measures of attention to and (rational) understanding of advertising messages for 50 years or more.

If, as seems likely, this turns out not to be how advertising works, then the industry needs to have some new tricks before admitting that the Earth is, after all, not flat.

Dr Heath shows that whilst it is essential to pay attention in school lessons in order to understand, process and store facts needed later for exams, this sort of goal-driven ‘Active learning’ is way too expensive in terms of effort and energy to be wasted on the thousands of commercial messages we are confronted by each day.

In practice a large amount of the information we deal with every day is processed in a shallow and inattentive way by ‘Passive learning’, which is bottom-up and stimulus driven. This type of learning isn’t sufficient for understanding or being persuaded but it is perfectly good at identifying and recognising things like brand logos, symbols, jingles and slogans.

But even low attention passive learning needs some sort of conscious awareness. In contrast, the vast majority of our brainpower and memory storage is to be found in the subconscious, which is effectively a vast store of ‘Implicit learning’.

Implicit learning is extremely fast, always on, unavoidable, attention-neutral and, crucially, not available to consciousness. But it is very much still ‘learning’, of the sort that can change our attitudes and behaviour towards brands. We just aren’t aware that it happened.

The book’s hypothesis goes further: The subliminal, the peripheral, the unknown and the not-recalled are by far the strongest influencers, with attention, explicit knowledge and persuasion having a minor role in advertising’s modus operandi.

This is because of the way our brain deals with any communication. Before the brain has to engage in any conscious, attentive analysis, it has already implicitly recorded (perceived) and conceptualised the stimulus. The conceptualisation process is one of linking and comparing what is perceived to values and experiences that we have stored in our minds across our entire lives, and it is entirely automatic.

Concepts are the way we attach meaning to what we perceive in the world, and they are often linked to emotions. To use one of the author’s examples, perceiving a red brake light would immediately and subconsciously evoke the concepts ‘danger’ and ‘slowing down’. Having perceived the stimulus and conceptualised it, we then have to react to it (or ignore it), and this calls for analysis. This is the familiar slow ‘System 2’ thinking of Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast & Slow, leading us to the most appropriate action such as swerving immediately or calmly changing lanes.

The key to understanding why System 2 isn’t how we process most brand communication is this: by raising a proposition to the level of consciousness, we open it up to all kinds of rational ‘counter-arguments’ why it might not be true. Conversely, stimulus that enters our sub-conscious mind and finds a well-worn pathway to an implicitly-learned ‘concept’ there, determines our attitude and behaviour towards the message sender (as long as we have passively learned who that was!)

Neatly explained in an earlier (and highly recommended) review of this book by Inspector Insight: ‘We actually pay less attention to emotional advertising and not more, and this is why it is so effective. When we pay less attention, we are less able to counter the messages with reasoning and simply soak it up. Emotions in advertising might work precisely because we do not think such messages are important.’

So how ‘important’ and ‘persuasive’ is strategically designed branded packaging? Our brain decides ‘not very’, but lets every detail of the design flood into our subconscious memory. Here it attaches itself to our stored concepts and brand ‘engrams’ (the collected pathways that already include the brand memories we have), and this is when the magic happens.

The design stimulus presents itself, in the words of Thomas Hine, author of The Total Package: ‘in an instant, as an old friend or a new temptation‘.

Both impressions are hugely valuable, so for the Innovators and Challengers out there, think of the truly transformative packaging examples in your world. They will always be richly laden with powerful concepts (stories, archetypes etc.) that everyone’s subconscious already knows intimately.